The Immovable Rock and Silent Tree

Jennifer mentioned the ever present discussion of whether God can create a rock that He cannot move and the (even more pressing) question of whether a tree falling with no one to hear it would make a sound. That gave me an idea, what if Aquinas had answered that first question and Anselm, the second? I think it'd sound like the following.

Of course, Thomas — being the Angelic Doctor — already actually deals with the issue in Summa Theologica 1.9.1 under the first article of the question concerning immutability. But, I decided it would be more amusing to have Aquinas deal with the issue directly, so hear is how I expect it would have gone:

We thus proceed to the first article.

Article 1. Whether God can create an object too large for him to move?

Objection 1. It seems that God can create an object too large for him to move. For as the Philosopher says (Metaphysics ii) “matter is in everything which is moved.” However, as was already admitted in an earlier objection (ST 1.9.1), there exists things that are not made of matter. Therefore it seems God could create an immovable, immaterial rock.

Objection 2. Further, it seems that movement belongs to only things that are not already perfected, but it cannot be said that nothing God creates is already perfect. Therefore it seems that God can create an immovable rock.

Objection 3. It is clear from the Sacred Scriptures and the Magisterium of the Church that God is perfect and all powerful, for as the Evangelist reports, the angel said to the Blessed Virgin Mary, “Nothing will be impossible with God.” Therefore it seems that God can create an immovable rock.

On the contrary, Augustine says (De Nat. Boni. i), “God alone is immutable; and whatever things He has made, being from nothing, are mutable.” Therefore no creation of God can be immutable.

I answer that, although God is all powerful, He is also simple (ST 1.3), therefore all of God's essence and existence are one. If God's essence and existence are one, He cannot do anything in His will that would cause His essence to be in conflict with His existential actions. The resultant action of discord from God creating something that He Himself could not move would bring his existence into conflict with His essence, but a thing cannot be and not be in the same substance.

Moreover, a thing that is in conflict with itself is not as perfect as a thing that is not in conflict with itself, but we know that God is perfect, for as the First Principle, He is pure act and pure act is most perfect. If He were not pure act, He would not be the First Principle, but rather a Second or Third Principle, as is clear from the Philosopher. But, it is written “Be you perfect as also your heavenly Father is perfect” (Matthew 5:48). Therefore God is perfect and, as pure act, can move anything that is not pure act, which is everything other than Himself.

Reply to Objection 1. As I have related before, the immutability of something depends not only on the physical movement of matter, but also the ability of the object to be made more or less act. Everything that is not the First Principle does not have necessary existence, therefore, there is some time that the rock did not, or will not, exist. Therefore, because philosophers treat conversion from potency to act as movement, the immovable rock is only immovable so long as God grants it act, which he may cease to grant it at any time.

Reply to Objection 2. Although something may achieve its ends, and therefore cease movement, it only achieves it thusly as God has intended it. Nevertheless, anything that can possibly not be, will not be at some point, whether prior or future, and therefore the rock is not immovable regardless of whether it ceases movement at the achievement of its end.

Reply to Objection 3. Nothing is impossible with God, but the impossible cannot be because it is nothing. For something that conflicts with its own nature cannot actually exist, and therefore does not actually exist, nor can the idea of its existence even be pondered. Anything that has existence neither in potency or actuality can be said to truly be “nothing” and therefore, is not something that is impossible with God.

Anselm's Lost Appendix in Fides Quaerens Intellectum Dealing with Falling Trees

“The fool says in his heart, 'if no one is around to hear a tree fall, it does not make a sound.'”

O most perfect newly fallen tree, how marvellous it is that you should fall with clarity and make it so that even a fool can see his folly in this statement! For it is clear that you could not have fallen without making a sound. For you are the most perfect fallen tree that can be imagined. However, the most perfect fallen tree that can be imagined is a fallen tree that has made a sound as it fell. For if the most perfect fallen tree fell but did not make a sound, then a more perfect fallen tree, which did make a sound, could be imagined, and you would not be the most perfect fallen tree.

But you are the most perfect fallen tree, not because someone happened to be around to hear you fall, but rather because your status as the most perfect fallen tree made it necessary that you should make a sound as you fell. The fool denies the obvious when he makes the claim, for to say that the most perfect tree could fall and not make a sound, because he was not there is foolishness! To suggest that the most prefect fallen tree is only most perfect because of something outside of its perfect falleness is contradictory to the idea of the most perfect fallen tree, for if the most prefect fallen tree were only perfect because someone was there to hear it, I can easily imagine an even more prefect fallen tree that was perfect without need for someone to hear it.

Reading, Meaning and the New Testament

Reading through my first Greek in Exegesis assignments was not an exercise that was all fun, but parts of it were an absolute delight, because they touched on one of my favorite subjects: literary criticism. So, I thought I would mull over some of the ideas in the book and essays as a way of walking through the major schools and, ultimately, showing why I've ended up in the critical school I am in. This may prove further to Brad that I am sick.![]()

What got me started on this was that Wallace remarked in his text that language is cryptic and symbolic, which is something dangerous to say around a person who is recovering from a severe case of deconstructionism (that's me). Admitting language is cryptic and symbolic draws us into the territory of Deconstructionism. The essays rounded things out and helped soothe my other critical interests, incidentally, but I had to slow myself down lest my inner Deconstructionist get too excited.

The Deconstructionist, as well as the New Historicist, rejects the absolute of meaning because we observe that the meaning is lost “in the slippage of the signified from the signifier.” This is essentially a fancy way of saying that given any word (a symbol) it inevitably will shift from the intended meaning of the author. We can observe this quickly in two ways with respect to the Bible: first, well known verses have become so well known as to have obtained proverbial status, hence granting to them an independent status that does not exist in their original state (whether translated or not). Second, the statements have been pulled out of the context of first century Palestine, as such regardless of how much we try, we cannot reconstruct the mindset of the audience.

Ok, so language is cryptic, why does all this nonsense about author-text-reader really help at all? Well, I am glad you asked. Basically, as one of the authors said — I think it was Joel Green — Biblical interpretation (and, I would add, literary criticism in general) has gone through some marked phases in the modern and post-modern periods.

Let's journey down one path tonight, and we can pursue the others soon. The realm of interpretation actually has more than three sides, it actually has five: author, text/co-text, reader, intertext and reality. Understanding these explicitly, rather than taking them for granted, is extremely helpful, I believe.

The Enlightenment Project's sense that everything could be understood brought in Old Historicism, which in the context of the Bible, led to attempts to determine the original authors, their motives and their accuracy. It is also related to the Quest for the Historical Jesus. This is the school of both the Academic Study of Religion and classical liberal theology. It seeks, for example, to determine how Mark, the Q text and other sources were used by Matthew and Luke. This is, clearly, a focus on the author.

What is good about this school is that it forces us to consider the intent of the authors. God chose human authors; He did not need to do that. So why did He do that? Presumably, He did so because He could use their unique personality traits to cover important angles. Mark is short and apocalyptic. Luke is the detail oriented, literary guy. Matthew is interested in Jesus's relation to Judaism. John (or, more properly, perhaps, the Johannian community) is in the Kingdom of Heaven already, at least in spirit. Each has his own purpose and style.

Even controversial theories, such as the isolation of Q (which is abbreviated from Quelle or source) from shared passages in Matthew and Luke is fruitful. The basic premise is that we can find identical or highly similar passages between the two Gospels, pull them out of the existing Gospels, and get some idea of what the earlier source both writers used looked like. It does not seem far-fetched to believe that there was an earlier source upon which the two Evangelists drew. But, should we reject that, it still causes us to question why God led the two Evangelists to frequently word-for-word copy each other, while also frequently not doing so. Perhaps it is for emphasis on important topics, if so, all the better that we pay attention, isolate these passages and try to exegete them.

I reject this school tenderly, as it was the first critical school I applied intentionally as part of my time as a Religion major. I later used it — or tried to, anyway — in my interpretation of literature too. I battled long and hard to maintain my Old Historicist sensibilities, but ultimately I believe it is chasing after the wind. Nevertheless, its attention to the details of ever important cultural context are not to be forgotten. They will return when we reach a different school, later on.

A Week with the iPhone

After a week, I can still say I love this device. I'm working on a full fledged review for OFB, so I won't go into details, but all I can say is that despite the well publicized limitations, the device is such a pleasure to work with, one forgets about those things. There are a few complaints I have, but all of them are software related and could easily be fixed when iPhone OS 1.1 is pushed out sometime (I suspect) in the near future.

I setup my visual voicemail today and was surprised I didn't have to encounter a single voice prompt menu to do so. The iPhone recorded my message and set my passcode all from its own interface, then sent both the recording and the passcode to AT&T for me. No “press 1 to save your message, press 2 to hear it, press 3 to rerecord your message.”

I am a bit paranoid to walk around with this thing. I wish AT&T would offer its phone insurance for it. But, I figure I carry my laptop around all the time, so why not a phone?

Continuing My Tradition: Fireworks Tent Reviews

I shall offer my last minute fireworks shopping advice again. If you are going to be out and about tomorrow and need some fireworks, don't just go anywhere. I recommend the following two stands this year, which have garnered praise from me previously:

- Fireworks City, but not just any Fireworks City. In general, I don't recommend Fireworks City, but if you come over into St. Charles via I-70, and turn toward the former Noah's Ark restaurant (it still looks like a big boat), you'll notice two Fireworks Cities. One in the Noah's Ark parking lot, another between Noah's Ark and QuikTrip. That second one is the one you want to visit. The owner, and everyone else, is extremely helpful. If you should happen to talk to the owner (I do not know his name, I'm afraid), mention that you were referred by the seminarian who comes in there every year and has been slowly moving towards bigger fireworks and likes fountains.

This tent carries some of my favorites I've not even seen elsewhere, such as the Black Cat Reloadable Fountain and Black Cat Nuclear Meltdown. Also, if you are looking for something pricier but extremely impressive, checkout the Quadrific artillery shells. They are, as you might guess, shells with four separate breaks. Breaks are the neat effects you might see in a professional show that light up the sky in different shapes, such as a “chrysanthemum.” Also good are some of the Black Cat larger fountains, such as the “Mammoth Fountain.” They also have the best spinner (a wheel that is mounted to a pole) that I have ever seen — I cannot quite remember the name, but it has a giant eye on it — it's called wild eyes or something like that — and it lasts forever.

- Red Dragon — the owner's name is Tim, so how can it not be good?

The tent is located off of Mid Rivers Mall Drive (which runs from I-70 to Hwy. 94); if you pass St. Charles Community College coming from Hwy. 94, it is a short distance further, off to the left, back in a field. There's another tent across the street, but don't go there, drive back to Red Dragon. Tim is very animated in his descriptions of fireworks and was quite helpful. Though I bought most of my fireworks at Fireworks City (actually, I must admit I bought most of them last July 5, for 50% at Fireworks City…), Tim recommended several that I had not heard of before that were reasonably priced. These included a $7.50 8 shot and a $5.00 cone that he says will shoot up 20 feet.

The tent is located off of Mid Rivers Mall Drive (which runs from I-70 to Hwy. 94); if you pass St. Charles Community College coming from Hwy. 94, it is a short distance further, off to the left, back in a field. There's another tent across the street, but don't go there, drive back to Red Dragon. Tim is very animated in his descriptions of fireworks and was quite helpful. Though I bought most of my fireworks at Fireworks City (actually, I must admit I bought most of them last July 5, for 50% at Fireworks City…), Tim recommended several that I had not heard of before that were reasonably priced. These included a $7.50 8 shot and a $5.00 cone that he says will shoot up 20 feet.

They have 2 Cool, which is one of my personal favorites, as well as a lot of others I've not tried but which sounded very good.

And, while you can't find it at either of these tents, if you visit others look out for Just Another Stinking Fountain (J.A.S.F.), the best fountain under $10, period. Maybe the best at any price. I first discovered it out in Washington, MO, one year. I know Fireworks Superstore out by Hwy. 100 and I-44 in Gray Summit has it. So does a small tent off if you turn off of Hwy. 94 onto Central School road and make a right at the school. It is located just a little ways down the road in a Huck's gas station parking lot. It is worth looking for J.A.S.F.

Greek

Greek is a paradox. On the one hand, now with some background in it from years ago, a whole year of undergraduate Greek and the better part of a year of graduate level Greek, one would think I'd finally be comfortable with the language. Up until recently, I didn't think it would ever happen; nevertheless, even without that, there is something amazing about reading a so-called “dead language” and bringing it back to life, especially when one realizes the words one is reading are the words God inspired. If, as Christians believe, the Bible is God's written account of His entering into this world, how amazing it is to see a grammatical construction — even if it is extremely frustrating — and think, “wow, that was written by the author of John, it is not an attempt to reconstruct what was written by the author of John in English. This is the real thing.” A frustrating periphrastic construction can suddenly seem almost exciting (admittedly, it is not always so).

In the midst of that, as of this weekend, I finished translating the book of 1 John for class. I've read through all of 2 John and 3 John in Greek as part of an assigned 10 minute devotional reading each day, and I've read some interesting key parts of the Gospel of John for the same assignment (you can read anything Johannian you feel like, other than Revelation). Doing that much translation — and I've tried to translate all of 1 John twice in the last month, once on the official class scratch paper, and once on the final assignment pages — along with the timed, non-translated reading, I realize I am not yet thinking Greek, but I am beginning to. I can anticipate common phrases used in these books. When I do not recognize a word, often I can figure out enough from the rest of the words to know what it means with some degree of certainty — it is starting to feel more like reading unmodernized Chaucer than reading untranslated Beowulf.

That's pretty neat; I'm excited. I'd still like to expand into Classical Greek, but one step at a time…

Hmm...

Some times I wish I'd be a bit more daring; potentially interesting things get lost in the midst of over thinking them. Tonight was one of those nights. Of course being tired and having a headache didn't help, but I can't blame it all on that…![]()

Interestingly, that fits a line from Lee Ann Womack's song, “I Hope You Dance,” which I heard played tonight: “Never settle for the path of least resistance.” Yes, that is indeed tempting to do.

I hope you never fear those mountains in the distance

Never settle for the path of least resistance

Living might mean taking chances

But they're worth taking

Lovin' might be a mistake

But it's worth making

Don't let some hell bent heart

Leave you bitter

When you come close to selling out

Reconsider

Give the heavens above

More than just a passing glance And when you get the choice to sit it out or dance

I hope you dance

The Little Black Box

I have in my possession one of the most coveted items of the year, and certainly the most talked about of this day. Yes, that would be an iPhone. In Apple’s usual style of quiet elegance, the box sits there revealing little (as if there was much that has not already been revealed through months of slow leaks of rumors). It is nearly begging me to open it, much like its call beckoned me into the AT&T Mobility store earlier this evening despite my better judgment. I have it, but do I open it? Read my musings on Open for Business.

QuickMem Greek

For my fellow members of NT 302 Greek Reading (or anyone else tinkering with Greek), you may find this tool handy; it is a freeware flash card program that lets you bring up words for quizzing based on their usage frequency, as provided in the late Bruce Metzger's lexical aids. It's a pretty nice tool, and it works great on Mac OS X, as well as Windows (a Linux version is also available, though I have not tried it). It is not quite as well polished as Crosswire.org's flash card program, but the frequency selection seems invaluable.

The Approach of the iPhone

OK, how can anyone not want one? Sure, I'm not going to be there on Friday night, but that doesn't mean I wouldn't be delighted to be one of the writers who had a review unit in my pocket right now. The rate plans seem to shore things up nicely too, with unlimited data ringing in at a very decent price of $20/month. It is really unfortunate that the phone does not support 3G data, because with it being EDGE it won't be nearly as beneficial, but… that's for iPhone 2.0. The support for MS Exchange that has been revealed today also looks like it should help ease some concern about the phone's capabilities.

It's still a lot of money, it still lacks some things I wish it had, but, I can't say I don't find it tempting all the same. It may be a “status phone,” but it is intriguing for ever so many additional, vastly more important reasons.

Theological Stock Exchange

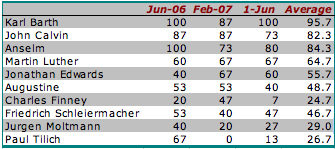

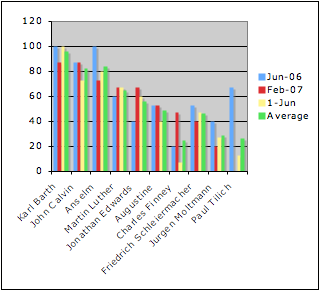

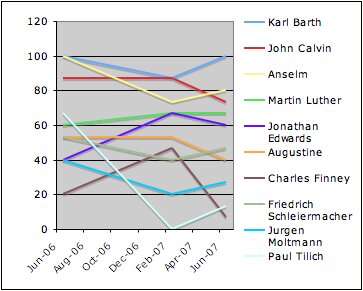

Dr. Lucas posted his results on the “Which Theologian Are You?” quiz, which prompted me to take the quiz again. I've taken this quiz two other times that I could find in my blog archive (I thought I had taken it even more). At any rate, there is some variation — beyond the basic result that I am always Barthian first. Happily, my second favorite theological saint, Anselm traded higher, returning to a second place position behind Barth (if Aquinas, my if-I-were-a-Catholic-he'd-be-my-patron-saint, where in the survey, he'd probably score high on my graph too). Oddly, while Calvin traded high in February, perhaps rallying from influence of Covenant, he fell to a new low this month. Barth rallied from a dip, to return to his previous high of 100%. Luther isn't terribly interesting — he stays pretty stable. Unfortunately, Tillich rose again from the depths of 0% and is now busy making my theology more ambiguous again: my theology is not, but rather is; it is not an existential thing, but rather an existential question; it is the ground of theology, creating a strict sense of complete dependence on theologians, particularly those that focus on kerygma rather than apologia. cough

Below are some charts for the statistically inclined. Post your own results in the comments (or a link to your own results on your blog).

| You scored as Karl Barth, The daddy of 20th Century theology. You perceive liberal theology to be a disaster and so you insist that the revelation of Christ, not human experience, should be the starting point for all theology.

Which theologian are you? created with QuizFarm.com |